All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

What's the loudness war?

Published onJune 17, 2021

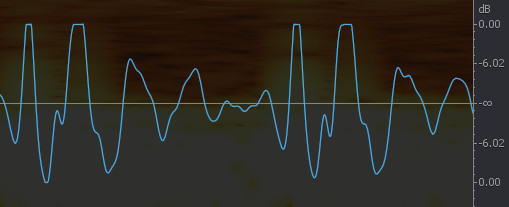

Take a listen to these two audio excerpts. Which do you prefer?

If you have a preference, it’s probably for the first one. The second recording is the exact same, but it’s just a tiny bit (2dB) quieter.

People prefer loud. When all other variables are kept constant, listeners reliably prefer the sound of a piece of music when it is played back at a higher volume versus a lower volume (until it starts to actually hurt). Over the past several decades this psychoacoustic phenomenon led to the emergence of music production techniques driven by a “louder is better” mentality, and a situation commonly referred to as The Loudness War, or The Loudness Race. Let’s pin back our ears and dig into how we got into this war, the major events, and how it ends…

How did the loudness war start?

In the beginning, when analog recordings were made into vinyl records, the grooves had to be fairly large to provide a good signal level relative to the surface noise. However, physical limitations with the cutting lathe meant the signal couldn’t be too large. Too wide of a groove reduced the maximum duration of the record, and large amplitude swings could bounce the needle, causing other problems. The mastering engineer took the artist’s finished songs, looked for the peak amplitude, and scaled the grooves accordingly.

Cut to the 1960s: Jukeboxes were popular, and louder records stood out from the rest. Audio pioneers The Beatles were apparently aware of this, and ordered a special device into Abbey Road Studios to help them compete with the louder Motown records coming across the Atlantic: a Fairchild compressor limiter. This is a classic example of an analog dynamics compressor—an audio device that behaves like an invisible hand on the volume control, to make the output more uniform.

A compressor first reduces the level of peaks in the audio signal (without affecting the signal below a defined threshold), then applies fixed make-up gain to bring the peaks back to their original amplitude. The result is an increased average level—linked to how we perceive loudness—with an unchanged peak signal amplitude. This type of signal processing reduces dynamic range in favor of overall loudness—basically, the difference between the quietest sounds and the loudest ones is reduced. If it gets extreme enough, this can make music sound a lot less natural (more on that in a bit).

What happened with the switch from vinyl to CDs?

CDs started slowly taking over from vinyl in 1982, as new recordings and back catalog material were transferred from analog masters to the new digital medium. In this context, digital audio differs from analog in two notable ways: it has a much lower noise floor (so low in fact that CD was the first medium to have a larger dynamic range than live music), and it has a well defined maximum peak amplitude that cannot be exceeded. If part of an audio signal exceeds that theoretical limit, the sound just “clips” (the waveform is squared off), and the peak of the waveform above the limit is lost, effectively becoming a tiny burst of noise—not pleasant at all.

See: High bitrate audio is overkill: CD quality is still great

Because of this, engineers were initially extremely cautious with the signal level on CD releases, allowing plenty of headroom. However, it didn’t take long before the “louder is better” mentality crept in once again. It was well understood from the vinyl days that once the signal peaks did hit that maximum allowable amplitude, the average level, and the perceived loudness, could be further increased by applying more compression and gain to recordings. Compression (not to be confused with data compression) meant peaks would more frequently get close to that maximum amplitude ceiling—And it turned out that occasional clipped individual peak samples weren’t really audible to most people.

During the 1990s, some engineers leaned into this approach and made their work noticeably louder. Making a loud record isn’t inherently a bad thing—the sound of heavy compression basically defines some musical genres— but there are tradeoffs. However, as CD changers became more commonplace, nobody wanted to release a CD that stood out as “the quiet one”—Your music would sound boring compared to the louder records. So the average loudness of CDs rose over time, samples clipped more frequently, the loudness war intensified, and dynamic range kept shrinking.

How did digital signal processing impact the loudness of music?

Around this point, several technological advancements became widespread in sound production: digital outboard limiters, digital audio workstations, and audio plugins. These allow for more extreme manipulation of dynamics. By employing what is known as “look ahead,” digital limiters can adjust the level while anticipating the incoming signal’s waveform, responding faster and with more precision than analog devices. This enabled “brick-wall” limiting, which effectively clips the signal at a point just before it reaches the theoretical volume limit. This process shaves off signal peaks and makes the top (and bottom) of the waveform look like it’s hit a brick wall. It doesn’t sound as bad as severe digital clipping, but it doesn’t sound good, and it gets easy to recognize. The prime example of this technology is the Waves L1 Ultramaximizer, the napalm of the loudness war.

These tools meant that, starting in the mid-’90s, engineers could make their tracks significantly louder than before. As those brickwall limiters were pushed harder, the sound became increasingly harsh. (What’s The Story) Morning Glory by Oasis is considered a landmark example of detrimental amounts of compression, combined with extreme limiting, to create something absurdly loud.

What other records are considered casualties of the loudness war?

Efforts to increase loudness in response to these brickwalled albums resulted in countless casualties of clipping and audible distortion. CDs were pushed more and more to compete with one another, which led to compromised releases.

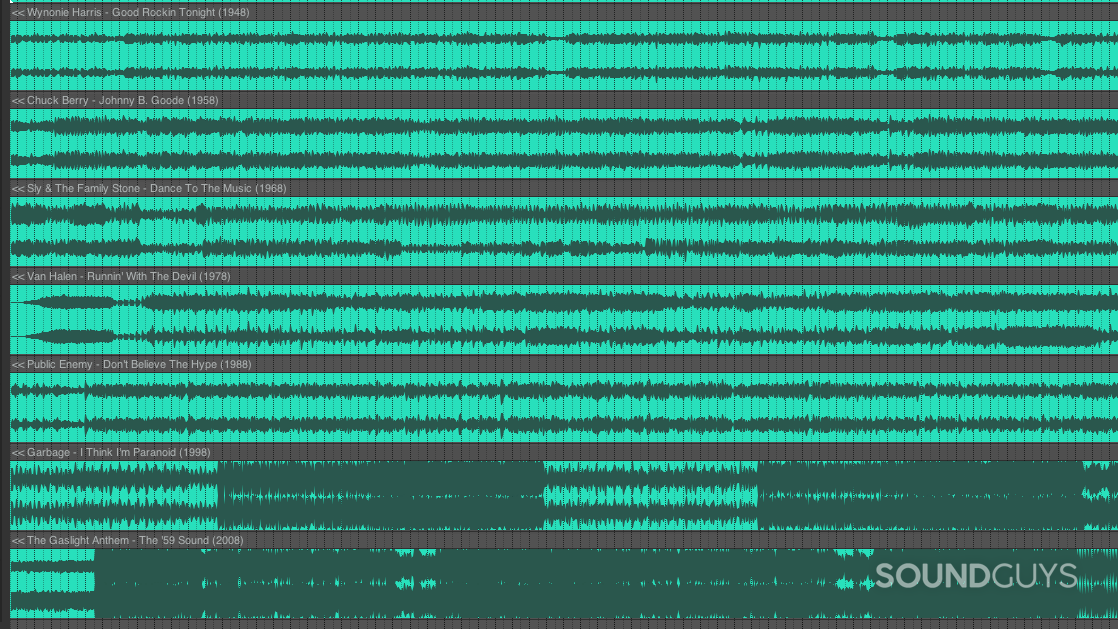

Open some songs from different eras in your favorite editor and take a look at the waveforms. Most music that predates the 1990s will have very jagged lines and resemble Christmas trees laying on their sides. Music mastered to be loud will look almost like a hamburger. There won’t be many peaks or valleys, just pure, over-compressed sound-patties: Those peaks and valleys represent differences in the peak loudness in the song (the dynamic range). When there are no differences, your brain starts to simply register the stimulus as noise.

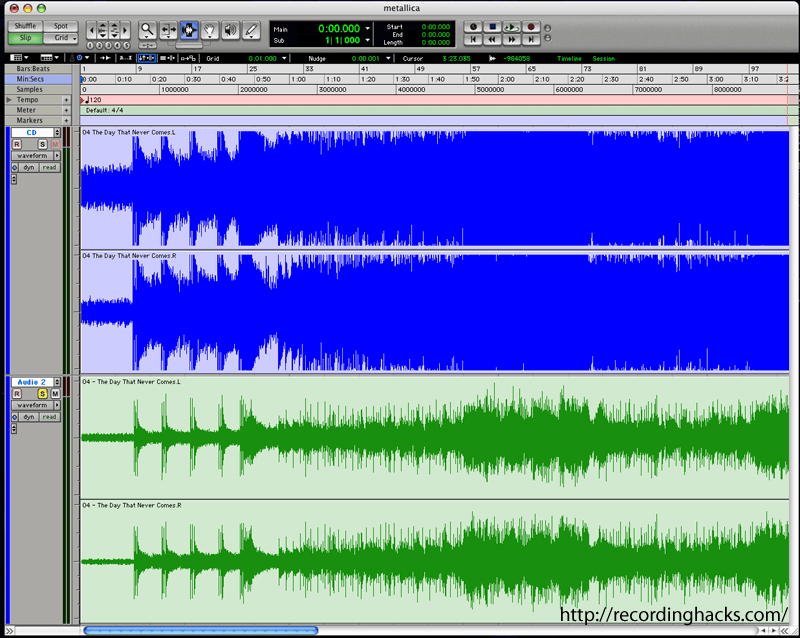

The most frequently cited victim of the Loudness War is the Metallica record Death Magnetic. This was so dramatically over-compressed and brick-walled on its initial release, that critics universally complained about the poor sound quality. The distortion was so apparent that anyone who listened to it could finally hear and understand the downsides of making CDs super loud. Effectively, Metallica won The Loudness War, and their beleaguered fans were ultimately its biggest victims. 2008 became the tipping point for the Loudness War, when an unlikely Hero showed music fans just how bad the situation had gotten. That’s right: the catalyst for the eventual backlash against loud music was Guitar Hero.

How did a video game wake people up to the downsides of loud CDs?

Guitar Hero III hit its stride as the prominent rhythm game of the year. To build the different layers of audio in the game, multitrack stems from the album’s recording were transferred from the recording studio. By piecing those stems together themselves, Metallica fans heard what the released record could have sounded like. All of a sudden, Death Magnetic actually sounded… kinda good. Although this moment of clarity didn’t actually end the Loudness War, it garnered enough coverage that many music fans began paying more attention to the issue.

The actual solution had already been developed in the background as a response to growing libraries of MP3 files from different eras, with wildly differing loudness levels. Replay Gain was introduced in 2001–the same year as the iPod–as the first volume leveling algorithm for music files. Soon after, most music library applications, including iTunes, could automatically perform analysis of tracks and write a loudness normalizing value into the file’s metadata.

How file metadata brought an end to the loudness war

Digital audio players and media playback software read metadata loudness values and adjust the playback level for each track accordingly–this has no negative impact on audio fidelity. The simple and ingenious way this works is to take the loud tracks and turn them down compared to the quiet ones.

This type of leveling technology quietly rendered the Loudness War moot: tracks made with cranked up compressors and limiters don’t end up any louder. Instead, you notice the lack of dynamics imposed by over-compression clearly when played alongside songs mastered without the “louder is better” approach, and you’ll likely appreciate the more open, dynamic material.

Today, streaming services all automatically apply normalized volume levels, usually based on “Integrated Loudness,” a measurement of loudness for the entire audio file. Most streaming services normalize to -14 LUFS (the standard unit of loudness measurement for broadcasting). If a song is deemed to be -8 integrated LUFS, it will be turned down 6dB, for example.

Loudness range, a measure of how dynamic a track is, also has a place in the audio file metadata. Application of these measures and leveling techniques are allowing the transition from a “peak normalized” audio world to a “loudness normalized” audio world, where you can switch from Aretha Franklin to Dua Lipa without adjusting your volume knob. Full adoption of this will eventually allow switching across platforms (music, movies, TV) without reaching for the volume control at all. It’s been a long time coming.