All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

How to write a song

Published onMarch 9, 2021

Whether you’ve played covers at open mics for years or you’re completely new to music-making, writing your first song can be a daunting task. However, songwriting can be extremely therapeutic and exciting. It can be intimidating to know where to begin, and even more difficult to know how to finish a song, but don’t worry: we’re going to take you through the step-by-step process of how to write a pop, rock, or folk song, using some of the simplest techniques. Hopefully this guide will kick-start your songwriting career.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on March 9, 2021, to add links to song examples.

What are the key components of a song?

If you’ve ever gotten a song stuck in your head, chances are the topline was what was replaying in your mind. The topline of a song is typically the most memorable part, and the most emphasized in your average rock song. It refers to the part of the vocalist: the lyrics and melody. However, that doesn’t mean the instrumentation of a song is unimportant—it can do much more than just back up the vocalist. Interesting instrumentals fill out a song and make it more engaging. There are plenty of famous guitar solos that you could probably recognize at the drop of a hat, like Jimmy Page’s solo in the song Stairway to Heaven.

Related: How to find new music

Depending on the genre and style you’re going for, you may choose to place more emphasis on the topline or the instrumentals. As long as you use some elements that make your song interesting, a few of which we’ll dive into today, then you can write a great song.

There is no absolute, linear songwriting process

Some songwriters begin a song by laying down a chord progression and building up from there. Other songwriters start by writing lyrics, and then fit it to a melody. Still, others can’t write lyrics unless they are attached to a melody. As an individual songwriter, you can also switch it up every time you write a new song. There is no singular best songwriting process, but if you conceptualize the main theme of your song, find a chord progression that feels right, then dive into some lyric writing, you’re off to a great start. After that, you can fill out musical embellishments and accompaniments however you like.

The basics of music theory

If you’ve played your instrument for years, you can probably skip this section. Even still, it’s always helpful to get a refresher on music theory, if it’s your first time composing music.

Start by learning about keys

When you start to write a song, the main component of music theory that you need to understand is keys—no, not piano keys, but musical keys. A musical key is a set of notes that makes up a scale—a subset of seven notes a piece of music revolves around.

There are twelve musical keys in western music, though some people argue that there are 24 musical keys, 12 major and 12 minor. If you take into account the fact that all major keys have a relative minor key composed of all the same notes, you could technically say either and remain correct. For the purposes of this guide, your song should exist within one of these keys. (Songwriters can change the key of a song halfway through the composition as a way to spice things up, or even several times, like in Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen, but that’s beyond the scope of basic music theory.)

When selecting a chord progression for your song, you need to make sure the chords exist within one key. If you have listened to western music your whole life, this isn’t something you need to worry too much about “messing up.” These twelve musical keys have been ingrained in your brain, and if you hear something that doesn’t conform to a key, it will sound off.

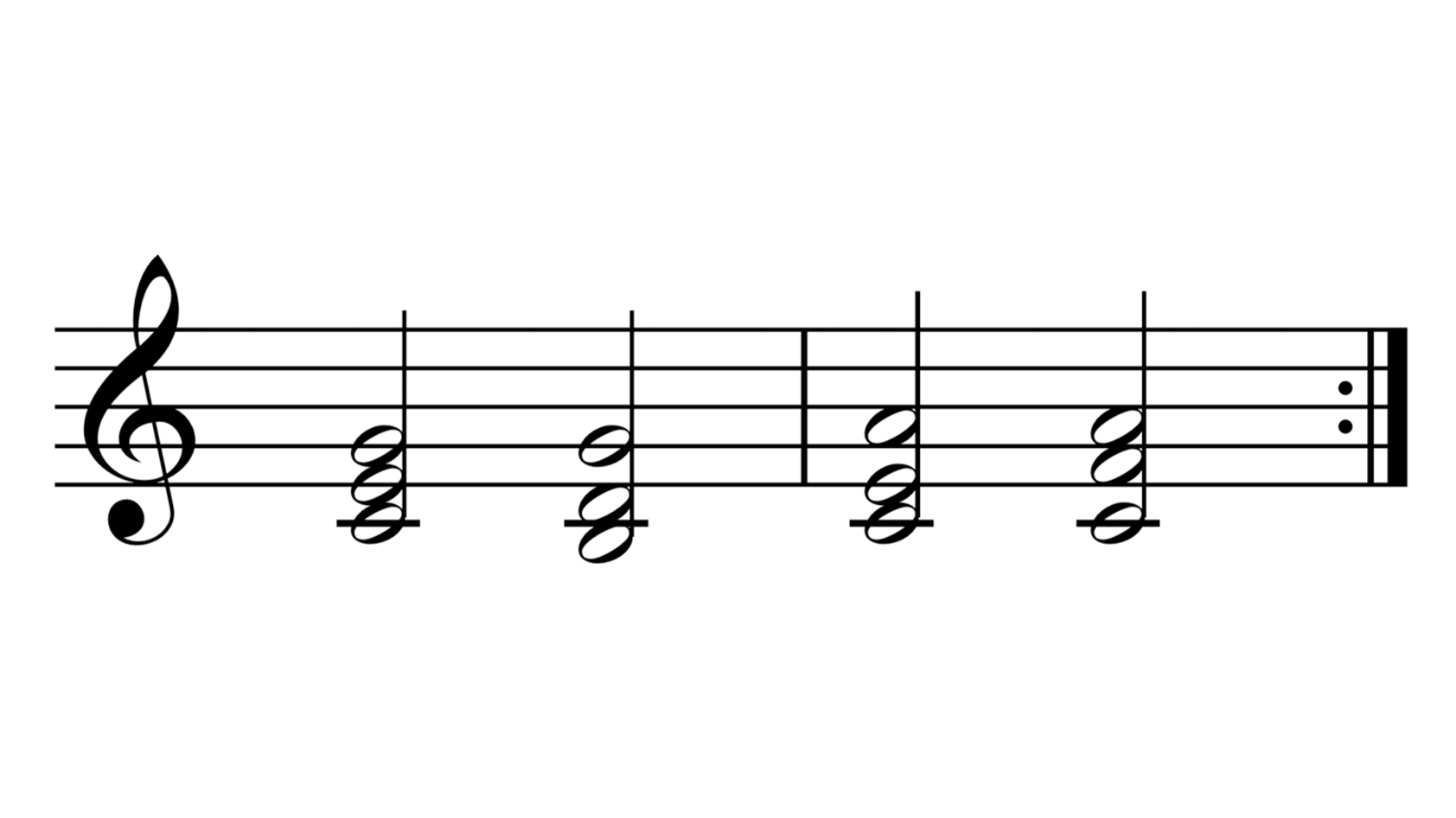

What is a chord progression?

The simplest and most common chord progressions follow predictable patterns. For the purposes of easy explanation, I’m going to use the key of C major as an example.

Within the key of C major, you have seven simple chords you can select from: C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am, B°. These chords correspond to their place within the scale—C is I, Dm is ii, Em is iii, F is IV, G is V, Am is vi, B° is vii° (The lowercase roman numerals represent minor chords in the C major scale, and the uppercase ones represent major chords in the C major scale).

One predictable chord progression pattern of a major scale is I-V-vi-IV, because it creates a sense of resolution at the end of the progression. If you’re struggling to come up with a chord progression, start out with this one for your first song. The chorus of Take Me Home, Country Roads by John Denver uses this chord progression pattern.

Another example of a common chord progression is the 12-bar blues progression I-IV-V used in countless songs, such as I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man by Muddy Waters.

There are many chord progressions you can use, and again, this isn’t something you need to worry about “messing up”. If it doesn’t sound right, you’ll know.

There is a simple song structure that’s great for starting out

Once you’ve brainstormed the general idea of your song’s message, it’s time to get writing. Many songs you hear on the radio follow this simple topline structure, and it can make planning your song more manageable.

Verse 1

Lyrically, a first verse typically sets the exposition of your song. How this looks depends on if your song has a linear narrative, or is more akin to a “feelings dump.” With our four-chord progression, the number of lines in your first verse is easiest to write in multiples of four. Your lyrics don’t necessarily need to rhyme, but they certainly can.

As far as melodies go, the first verse is probably the calmest section of the song. It eases your listener into the experience.

Chorus

A chorus is usually the most exciting part of a song. When it comes to the songwriting process, sometimes that means increasing the instrumentation, and sometimes it means writing a melody that gets stuck in someone’s head.

The pop song choruses often have many repeating notes, which makes them catchy because musical repetition is very pleasing to the ear. Take the chorus of INC. by Dori Valentine, which starts at 0:53. The first few lines of the chorus have many repeating notes, and the second section of the chorus, which begins at 1:11, has more drawn out notes. This creates a nice balance in the chorus.

There are other ways to integrate repetition into the chorus without repeating the same note consecutively. In Tally Ho by Walter Mitty and His Makeshift Orchestra, the chorus starts at 1:27 and is just the phrase, “Dude, I really miss you, yeah, dude, I really miss you,” repeated with the same melody a few times. It’s short and sweet but very memorable.

Verse 2

The second verse of a song can revisit the same melody and lyrical trajectory of the first verse, or it can switch some things up for added intrigue. For example, in Touch It by Ariana Grande, the second verse starts at 1:21 and begins with a similar melody to the first verse. Though, in the second part of the verse at 1:38, it switches to an entirely new melody.

Chorus

The second chorus can be exactly the same or a bit different from the first chorus. Some artists will make the second chorus have the same melody as the first chorus, but with slightly different lyrics, such as in Cig by Baby FuzZ.

Bridge

One of the most difficult things about writing a good song is making each line interesting so the listener doesn’t get bored. A bridge can really make a song special and shake things up mid-song, if it’s starting to get too repetitive. It is a section of the song notably different than the other formulaic elements. Whether that difference is in the chords, instrumentation, vocal melody, lyrics, tempo, or key, it can keep the listener engaged.

In Taylor Swift’s song Dear John, the bridge builds up to a swell of instrumentation at around 4:01. The bridge is very dynamic: it goes through a few crescendos and decrescendos, and continues the momentum into the final chorus of the song. The dynamism of this bridge adds significantly to the overall power of the song.

Chorus

In a lot of pop songs, the chorus repeats at the end of the song several times. This repetition makes the chorus stick in the listener’s mind even more. It also helps create a resolution to the song as a whole once the repetition ends. In Cool Girl by dodie, the end of the song is just the chorus repeating multiple times starting at 2:11, followed by a little instrumental outro.

You don’t have to follow a structure at all

There is so much music out there from so many different genres, and one of the best things about music is that it doesn’t have to follow anyone’s arbitrary rules. Just because you’re learning how to write a song doesn’t mean you must follow a formula. Take Nikes by Frank Ocean, for example. This is an excellently written song, and it doesn’t follow any structure. There’s no verse, no chorus, no bridge. It’s just a train of thought, and it’s beautiful.

Adding other elements

After writing the topline and basic musical structure of your song, you can experiment with adding additional elements. Take Scott Street by Phoebe Bridgers; in this song, a helicopter sound that comes in after Phoebe sings the phrase, “There’s helicopters over my head,” at 0:45. Later at 1:31, a dissonant violin enters and continues sporadically throughout the song. Then there’s the drum beat at 2:02, right before Phoebe sings, “I asked you how is playing drums,” and the choir-like harmonies sing, “They’re all getting married,” at 2:28. During the outro, the train whistles and other random non-instrument sounds pop in—all these things make the song memorable and unique.

Beyond just instrumentation, harmonies, and adding things in the raw stages of music-making, you can also add elements to your music in the recording and production stages. For example, the double-tracked vocals of Bon Iver’s re:stacks make the song so much more poignant.

Look to your favorite songs for inspiration

This guide by no means covers all the bases of writing music. It’s simply meant as a tool to offer inspiration and guidance for beginners. If you’re still struggling to begin, listen to some of your favorite songs; identify the different sections, and make note of your favorite aspects of the song. After doing this with a few songs, you should feel more directly inspired.

Once you’ve written multiple songs and are comfortable with the process, you may surprise yourself by what wonderful and creative ideas you come up with on your own. Happy writing!