All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

How to build a professional recording studio at home

February 4, 2025

It’s a Friday night, and your band has a killer song that you’ve rehearsed to a T. You want to make a home studio recording, but you don’t know where to begin. Don’t worry, we’ll tell you everything you need to know before you hit that red button, including what equipment you need, what equipment you can bypass, and what to expect during the process.

This article was updated on February 4, 2025, to include the latest information on recording software and hardware.

How do you pick a digital audio workstation (DAW)?

A DAW, or digital audio workstation, is a computer software program for mixing and editing audio. Excellent industry standard DAWs include Pro Tools and Adobe Audition, but these can get pricey depending on your subscription. You can get a free version of Pro Tools, called Pro Tools Intro, and amateur recording artists will find this good enough—unless more than 128 tracks are needed for a single song. Many introductory pieces of gear, like the Focusrite Scarlett Solo (4th Gen) come with entry-level recording software such as Ableton Live Lite, Pro Tools Intro+, and FL Studio Producer Edition.

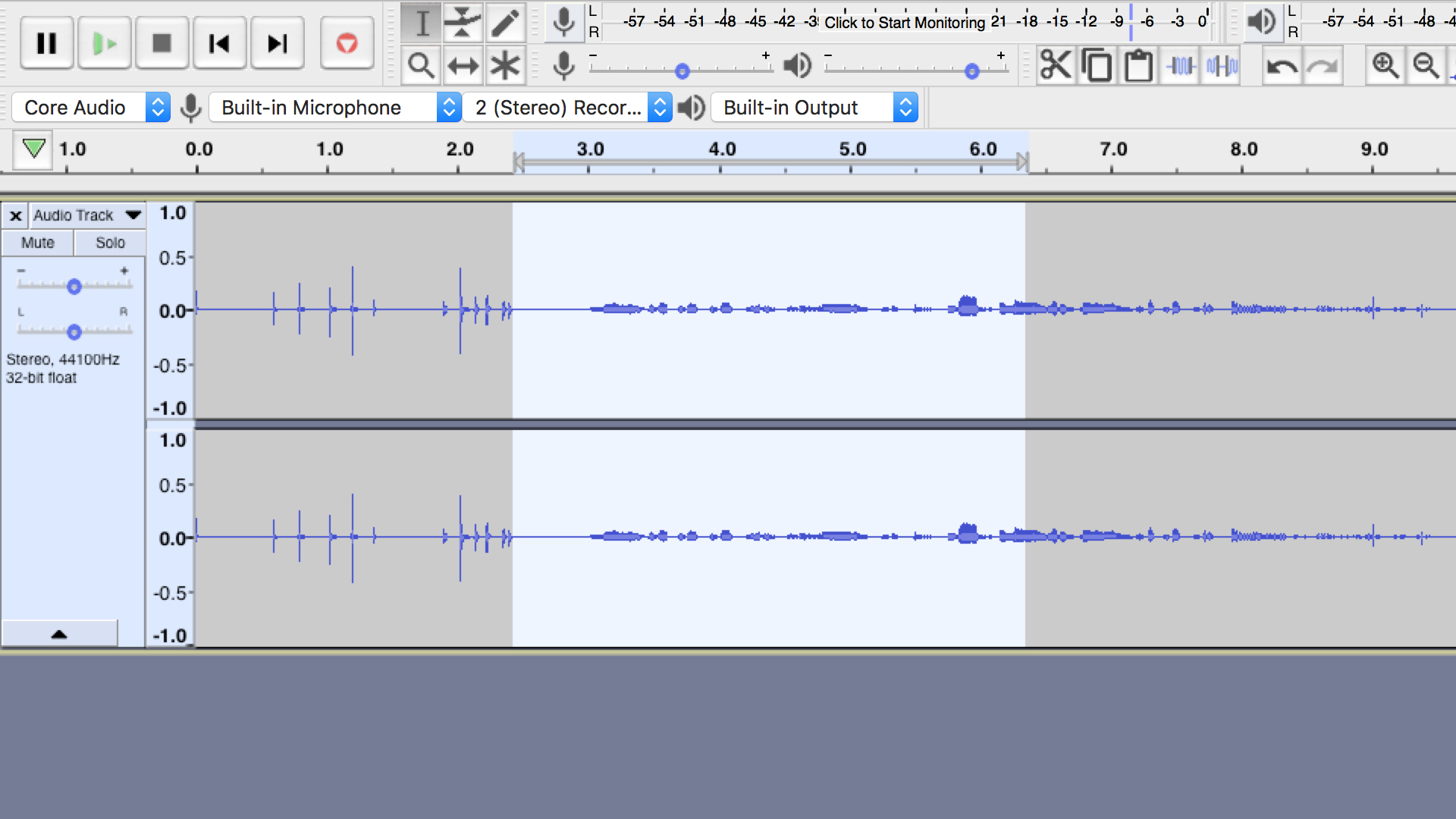

There are plenty of completely free DAWs out there, the most popular of which are Audacity (Windows) and Garageband (macOS). These work well enough but are missing comprehensive features that professional DAWs provide.

You can download third-party plugins and applications for greater control in Garageband.

With Garageband, it’s a little more difficult to keep your tracks organized than with a pro DAW, because Garageband lacks a mixer window. A mixer window displays your tracks along with their plugins and controls in a vertical view and allows you to monitor their levels. The same functions are displayed in Garageband’s track window, but this can get crowded when you deal with multiple tracks. In addition, where professional DAWs have intelligent software such as pitch correction, Garageband’s pitch correction software is rudimentary. If you try Garageband and essentially want an upgraded workflow, Logic Pro X is the logical step forward.

Audacity recently ran into controversy regarding the possibility of collecting unreasonable amounts of data from users. In addition, Audacity has its drawbacks: when you apply a plugin to a track, it alters the original recorded file. This is called destructive editing. With professional DAWs, however, effects are overlaid on top of the original file and can be removed later on. Some professional DAWs even offer plugins such as autotune, intelligent noise reduction, Flex Time (for when your timing goes slightly off), and other sophisticated audio processors that free DAWs like Audacity don’t include.

It takes time to get past the learning curve of any DAW, but ultimately, you should choose one that includes what you need for your style, and a few extras you could want down the line. A free DAW like Pro Tools First, Garageband, or Audacity is a great place to start.

You need to treat your room for home studio recording

When making a home studio recording, there are often unwanted noises picked up by your mics. Recording in an untreated room means the sound of outside road noise or air conditioning units could affect your raw recording. In addition, an untreated room will produce room resonances from sounds bouncing off flat surfaces and corners. These are easy things to combat ahead of time so you’re not wasting away with menial post-production tasks.

Fortunately, you don’t need to buy expensive equipment to mitigate these unwanted effects. If you’re not willing to spend any money on acoustic treatment, that’s fine. It’s best to record in a carpeted room with soft furniture and as few flat surfaces as possible; hard, flat surfaces are what produce unwanted echoes. At the very least, just tent a blanket over your head when recording vocals.

Record in a room in the middle of your house

The easiest way to reduce unwanted noise is to record in a room as far away from windows, and to turn off all fans and air conditioners. Once you’ve selected the room you’re going to record in, try clapping loudly several times from various spots within the room and assess if the sound produced is more of a harsh ringing or a nice reverb. As you continue to treat your room, you can use this clapping test again until the room resonances sound more like what you desire.

If you’re going to buy anything, get bass traps

If you’re going to invest in one specialized piece of room treatment equipment, it should be a porous bass trap. Again, this won’t transform the structure of your building or room, but it will do a bit to absorb bass frequencies. Be cautious though: cheap bass traps may very well be made from the same foam as your beloved family room couch. If you don’t want to invest in bass traps, a similar but lesser effect can be produced by placing soft pillows in the corners of your room.

Wall panels absorb unwanted echoes in the mid and high frequencies

Placing foam on flat surfaces can minimally reduce unwanted echos in your room. Some budget alternatives to purchasing acoustic panels are to encase your microphone with a foam shield or something made of soft material (like a blanket fort), or to prop your mattress up against the wall.

Diffusers are nice, but expensive

Diffusers prevent absorptive materials from sucking all the life out of your recording, because they scatter reflections off of flat surfaces that vary in height. This creates a more even dispersion of sound throughout the room, but they aren’t necessary for home studio recording, especially if your home studio is small and your budget is tight.

What makes a good microphone?

Before we get into the lowdown of recording different instruments, there are a few things you need to know when you’re looking to buy a microphone.

When shopping around for microphones, you’ll likely come across the XLR and USB varieties. An XLR microphone outputs a balanced analog signal, whereas a USB microphone outputs a digital signal. Generally, XLR microphones are better quality than USB microphones, though they are a bit more expensive and require an audio interface to do the digital conversion.

There are two main types of microphones—dynamic and condenser. Each is suited to its own set of use cases, and neither is inherently worse or better. Make sure to take a look at our breakdown of the best recording microphones on the market.

Dynamic microphones

If you’ve ever seen someone sing live, they were probably using a dynamic microphone. Dynamic mics are excellent for noisy environments because they can withstand loud inputs before distorting the sound. Most dynamic mics have internal shock mounts to reduce handling noise.

Their ability to withstand loud inputs also makes them great for recording loud instruments such as drums or electric guitars. Another reason to consider dynamic microphones: they don’t require phantom power, so you don’t need to worry about investing in a phantom power source (though most audio interfaces have them built-in anyways).

Condenser microphones

Condenser microphones are much more sensitive than dynamic microphones and are great for picking up very melodic instruments (vocals or acoustic guitars). Condenser microphones are not the best for recording very loud audio, because their sensitivity makes your recording prone to distortion. They require phantom power to operate, and this can be provided by an audio interface or a dedicated mic pre-amp.

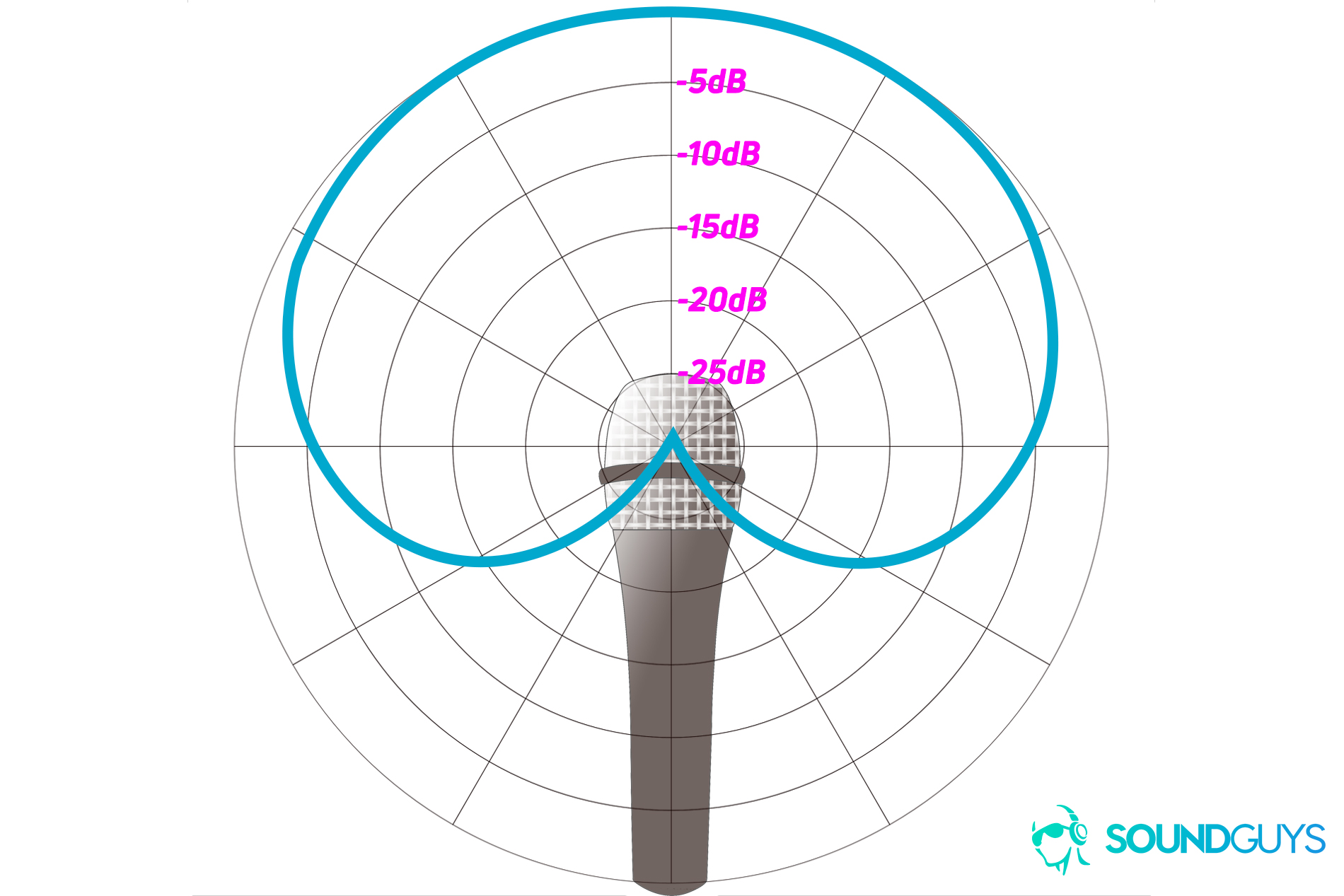

Polar patterns and placement

A polar pattern is a spatial field from which a microphone picks up audio. The most common polar pattern is the cardioid, meaning “heart-shaped” in Latin. Cardioid microphones record sound from what’s directly in front of them and slightly to the sides. These are excellent for recording vocals because they reject off-axis sound yet are allow for flexible placement.

Another fairly common polar pattern is omnidirectional which picks up sound from all sides of the microphone. This polar pattern is great for acoustic guitar because it registers room resonances and makes it sound more natural. Bidirectional pickup patterns record sound from the front and back of the microphone capsule, and stereo pickup patterns record sound from the left and right sides of the microphone capsule.

Frequency response

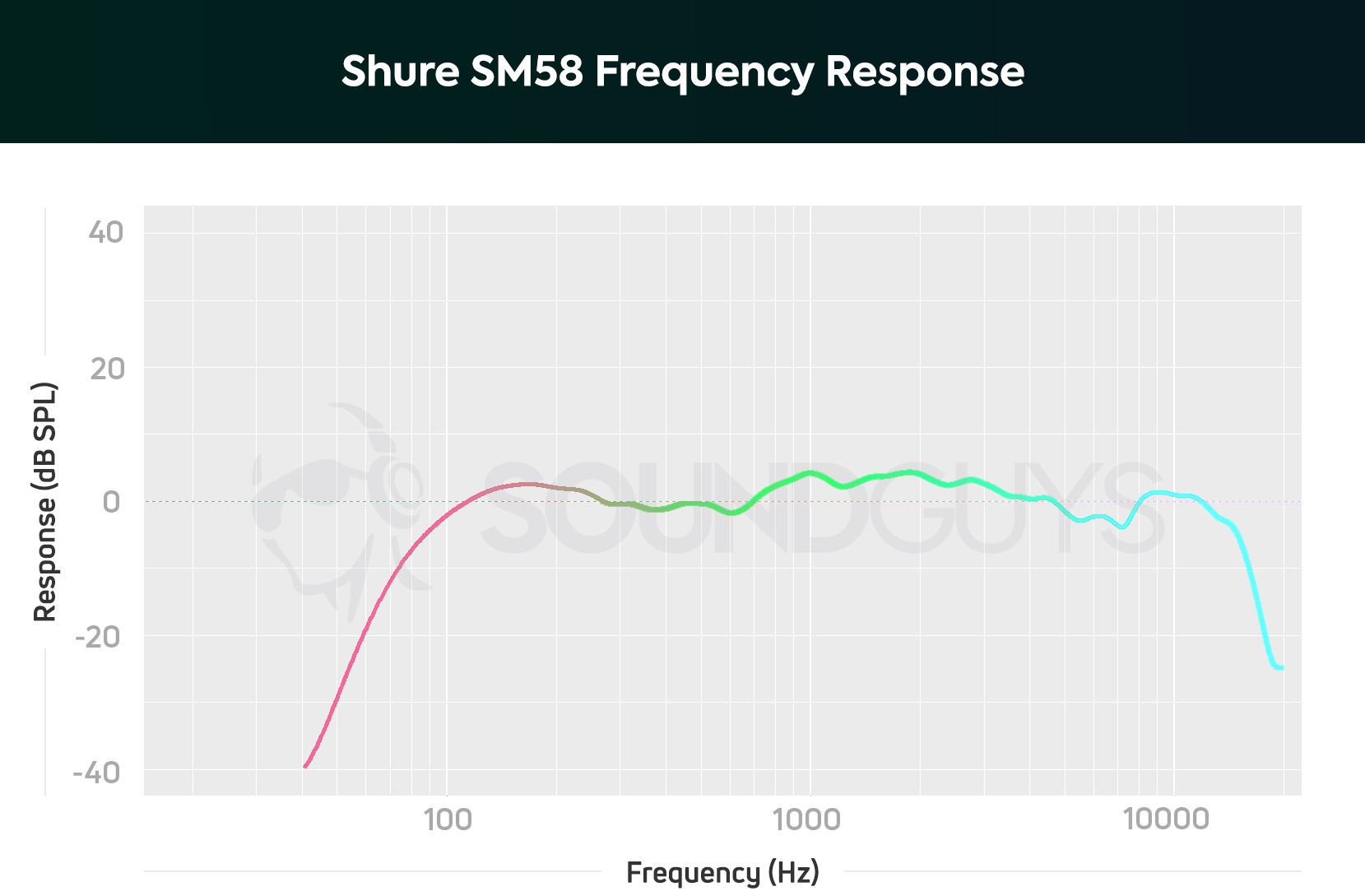

A microphone’s frequency response refers to how accurately the microphone can record different frequencies. In general, a more neutral frequency response (closer to the red dotted line) is better, because your audio will be reproduced as it sounds in the real world. However, many microphones have certain non-neutral characteristics in their frequency responses, such as bass attenuation to reduce the proximity effect (the over-amplification of bass frequencies due to close proximity to the capsule), or a slight treble boost to highlight the harmonic content of vocals and instruments.

Do you need an audio interface for studio recording?

XLR microphones are better quality than USB microphones, and you should definitely invest in one if you’re going to be recording music. If you’re recording from an XLR microphone into your computer, you’ll need an audio interface to digitize the analog signal from the mic into something your computer can understand. We recommend the Focusrite Scarlett 2i2: it offers 48V phantom power, which you’ll need if you’re using a condenser microphone, and comes bundled with software.

The Scarlett 2i2 allows for two simultaneous inputs, whether they are direct inputs from instruments or XLR from microphones. If you plan to record many instruments at once, or want to record acoustic drums, you should look into a larger interface such as the Focusrite Scarlett 18i20. Focusrite isn’t the only brand for interfaces out there, and you can browse our list of the best USB interfaces for studio recording to select the right one for you.

The ghost in the machine is actually just direct current (DC) power, supplied usually by your audio interface. These days phantom power is usually 48 volts. In the days of yore (mostly before the 1960’s) microphones requiring additional power would come with their own power supply units.

Phantom power is generally required for condenser mics. Dynamic mics don’t require phantom power, though sometimes they need more gain than their powered siblings in order to reach a useable volume. For such cases, check out the Cloudlifter.

How many microphones you need is not a one-size-fits-all solution

In an ideal world, you would have the funds to get a specialized microphone for every instrument, but most of us have limited finances. You can make a good home studio recording with a variety of mix-and-match techniques that save you some money. We’ll cover the most commonly recorded instruments—vocals, guitars, drums, and keyboards—and the various combinations of microphones you can use to record them.

However, if you know you’re only going to purchase one microphone, we recommend the Shure SM58. It’s affordable and sounds pretty darn good on a variety of instruments.

Shure SM58 speaking sample:

Shure SM58 singing sample:

Shure SM58 acoustic guitar sample:

Shure SM58 electric guitar with amp sample:

What microphone is best for vocal recordings?

Vocal microphones should almost always have a cardioid pickup pattern. A neutral leaning frequency response is ideal, since you want to accurately capture the voice. When making a vocal recording in your home recording studio, it’s usually best to use a condenser microphone, like the Rode NT1-A or Beyerdynamic M90 PRO X, because these are highly sensitive and pick up on treble detail. However, plenty of vocalists use and get great results from dynamic microphones such as the Shure SM58 or the Shure SM7b.

As for placement, your mic stand should be away from the walls of your room, but this matters less if you have premium acoustic treatment. You want to make sure you’re not singing with your mouth right on top of the microphone, because this will likely cause it to pick up plosives (-p, -t, -k sounds), fricatives (-f, -th sounds), create sibilant sounds (-s, -sh, -ch), and fall victim to the proximity effect.

Depending on the genre of your song and how loud you’re going to sing, putting about 6 to 12 inches between your mouth and the microphone is ideal. You also should invest in an external pop filter to further reduce these unwanted sounds and save yourself editing time in the future. If you’re pinching pennies, make your own pop filter by bending a wire coathanger (surprisingly, not the first appearance of a coathanger on SoundGuys) into a circle and stretch a set of pantyhose or nylons over it.

What microphone is best for recording acoustic guitars?

You can buy direct input boxes and use amp simulators, but the most common (and nicest-sounding) methods of recording guitars typically involve at least one microphone. Some audio interfaces have instrument inputs and do not require a separate device to achieve useable recording levels.

If you’re recording an acoustic guitar, a go-to way to get a nice sound is to place a condenser microphone directly in front of the soundhole of your guitar, and angle it towards the twelfth fret. A condenser microphone is better than a dynamic mic for the acoustic guitar because of its greater sensitivity; the twelfth fret placement allows your mic to record a good blend of low, mid, and high frequencies from your instrument. If you already have a condenser microphone for recording vocals, you can certainly use it for recording your acoustic guitar.

If you want to kick up the quality a few notches, you can make an X/Y stereo recording by touching two small-diaphragm condenser microphones’ capsules together at a 90-120° angle and mixing one as the left and one as the right channel. While this isn’t necessary to make a decent acoustic guitar recording, it is especially helpful in creating an engaging mix if your song doesn’t have a lot else going on besides guitar and vocals.

What microphone is best for recording electric and bass guitars?

When recording an electric guitar, you should use a dynamic microphone pointed at your guitar amp. The Shure SM57 is an excellent choice because it is affordable and sounds great, though the SM58 works fine if you already bought one. Point your amp away from any flat surfaces or walls to avoid reflections and phase cancellation. If you can place your amp on a platform it will help reduce acoustic coupling with the floor.

A mic placed halfway between the center and edge of the speaker cone, angled towards the center, is the most common practice.

When recording from your guitar amp, the capsule of the microphone should be facing the cabinet of your amp at some point on the speaker cone. The most common mic placement is halfway between the center of the cone and the edge of the cone; this picks up a good mix of low, mid, and high frequencies. To make the mixing process easier on yourself, it’s best not to record your electric guitar with reverb enabled on the amp, and to instead add reverb later in mixing.

Similarly, if your audio interface has a direct input for instruments, you can plug in and record your guitar directly to the DAW. Later when you have a good take, play it back and send the output from the interface to the input of the miked-up guitar amp. At that point, send the mic back to your DAW and hit record. Doing this allows you to customize your mic placement and tweak your hardware effects without sitting there for hours playing the same refrain over and over, only to discover you muddied the sound by too many effects or poor microphone placement.

What’s the best way to record a drum kit?

Recording drums in a home studio recording is very difficult, especially if you’re recording on a budget. This is chiefly because each individual drum often needs to be miked separately, some with two mics, and the kit at large needs to be miked as well. This is why unfortunately for most home studio recordings, an acoustic drum kit cannot be used.

If, however, you are determined to do this, you can get away with four microphones. Roughly speaking, this method worked for The Beatles. In editing, it will be more difficult to separate each drum and cymbal, but if you angle each microphone right you can reduce the amount of audio bleed.

- One dynamic microphone aimed at the snare

- One large diaphragm dynamic microphone for the kick

- Two, ideally identical, condenser microphones acting as overhead mics. Place them on a T-bar and in an array that points them over the cymbals and toms in a Y configuration.

Just remember that whatever side of the drum you mic determines whether it needs a phase inversion. If you mic the underside of the snare, for instance, it needs a phase invert. Think of it like physics; if you hit one side of the drum and the soundwaves have to travel to the other side of the drum before reaching the microphone, it’s going to have a slight mismatch with the other tracks without a polarity reversal.

For ease of use, we recommend either using virtual drum software or an electronic drum kit. Some DAWs have embedded virtual drum software. For example, Garageband allows you to select a smart “drummer” and adjust its level of complexity and the time signature of your song. DAWs like Garageband and Pro Tools also have MIDI drum plugins that give you more control and freedom to create, but you may want to invest in a physical MIDI drum pad or MIDI keyboard for ease of use. Some beats-oriented DAWs like Ableton Liveoffer more flexibility for making rhythm tracks than traditional DAWs.

If you don’t like the idea of playing drums with your fingers, an electronic drum kit may be the way to go. The one I have is the Alesis Drums Nitro Mesh Kit, which is (relatively) affordable and lets you enable stereo output.

How to record a keyboard

One great thing about digital keyboards is that they have analog outputs that can be plugged directly into your USB interface via a 1/4-inch cable. Some digital keyboards also have MIDI outputs, USB outputs, and stereo outputs, which can either be plugged into your audio interface or directly into your computer.

A MIDI controller does not have any internal “sounds,” rather it communicates with other sound generators, like software or synthesizers. The Arturia KeyLab 49 Essential should cover basically every use case (and then some). Modern-day MIDI controllers have USB connections so you can bypass the audio interface, and just directly plug in the USB.

Sometimes all you need is a DAW and a MIDI controller to make music.

Different DAWs supply their own virtual instruments, but you can find free and paid third-party ones out there that work easily with your DAW too. Your MIDI keyboard can trigger the sounds with virtually zero latency.

MIDI the acronym for musical instrument digital interface and it’s a language, which has been around since the early ’80s. It commands the sound generator (your software instrument) which note to trigger. If you hit middle C on your controller and your MIDI instrument will play the note. It’s incredibly useful once you introduce sequencers, or if you’re not a maestro pianist.

Later these recorded MIDI tracks can be converted to audio when it’s time to mix. The upshot of MIDI is that it’s extremely easy to edit compared to audio because it’s just recorded data. So if you flub a note you can select it and delete it, or select and shift it to the correct note.

It’s best to have studio monitors or studio headphones

While you will need closed-back headphones to monitor your recording as it’s happening, it’s always best to do your mixing with a set of studio monitors rather than headphones. Studio monitors produce a more accurate representation of your mix’s stereo image. With that said, sometimes the entry price to decent studio monitors can make studio headphones more attractive.

If you are going to use headphones to mix, studio headphones with a neutral-leaning frequency response will help you monitor, mix, and edit your music more accurately because the sound reproduced is true to what’s been recorded. Open-backed headphones more accurately represent sound than closed-back, but an affordable set of headphones like the Sony MDR-7506 is an industry standard. The AKG K371 and Sennheiser HD 280 Pro are additional budget options that sound great despite their low price.

As a reminder, it’s always a good idea to listen to your mix on a variety of output devices. Take your mix into the car, try it out with your noise canceling headphones, take a listen with your Bluetooth speaker. Doing so will help you get a better idea of what other listeners will hear when they play your song.

Making the actual recording

Now that you have your room treated, microphones set up, and headphones on, it’s time to record some music. First thing first: tune your instrument! It may even be worth replacing the strings on your guitar a few days before making a recording to ensure you get the best possible sound out of your instrument.

You will want to use overdubbing

Overdubbing is the practice of recording tracks on top of pre-recorded tracks. Recording a whole band at once can be very expensive and challenging. This requires a lot of microphones (and XLR inputs), sound-isolating panels, and perfectly in-sync musicians. Additionally, audio may bleed from an instrument into the wrong microphone, so you could have the sound of the snare drum on your acoustic guitar track.

Once audio has bleed, it severely limits the amount of post-processing that can be done to your mix and limits your song from having a studio-quality sound. In pro studios, this problem is usually prevented by placing miked amps in separate rooms from the drum kit, but because you’re working with a budget home studio, overdubbing is going to be your friend.

You should begin by recording the least melodic component of your song and gradually move up to the most melodic component.

When you start recording from scratch, begin with the least melodic component of your song, such as drums, and gradually move up to the most melodic component, such as vocals. Building a mix this way allows an in-sync outcome and makes it much easier for you to edit the song.

Whether you’re using a drum loop, playing an electronic drum kit, or recording acoustic drums, you’ll want to keep time with a click track; a click track serves a similar role as a metronome. In the event you do go out of time, fix it before recording other instruments. You can do this by quantizing or using something like Flex Time (which is in Logic Pro X). Alternately, just re-record that part and nip it in the bud, because recording another three minutes of drums that are already set up is easier than spending an hour messing with editing.

Gain levels are very important

Once you position your microphone in front of your instrument or in front of your face, you should test the input level, also known as the gain. Your USB interface and your DAW will likely both have gain meters, which indicate through green, yellow, and red lights if the volume is good. Green indicates that the input level is safe and you are not at risk of clipping, or distorting the sound. Yellow indicates that your audio will clip if your recording gets louder, and red indicates that you are clipping.

Generally, start by leaving your track level at 0dB gain. Incrementally up the gain on your audio interface to find that Goldilocks gain level before you record. You can later play around with the DAW mixer levels when editing.

Test your gain levels by playing or singing the loudest part of your song—it should be in the green, or just touching the yellow, at 50-75% up the meter. If your audio is clipping, it’s basically impossible to fix. So while you want “just right” for your gain levels, recording too quietly and in the green is more salvageable than too loud and in the red. Too quiet requires finesse (and usually plugins) to fix, rather than an automatic re-record because you clipped a track.

You will need multiple takes

When making any recording, it’s nearly impossible to get it right on the very first try, and patience is a virtue with this art form. To reduce the number of takes you have to record, make sure you rehearse your song a lot. The magic actually happens in the recording stage, rather than in the post-processing. Of course, post-processing allows you to add effects and adjust levels and panning, but if your original recording is bad, there isn’t an easy fix.

Sure you can add effects in post-production, but getting it right in the initial recorded track is where it counts.

Make sure you leave about five seconds of dead air before and after your recording. This will make it easier to trim your recording, adjust the EQ of your tracks, and to hear the approximate level of unwanted ambient noise that needs to be removed in the mixing phase.

What’s a good budget for home studio recording?

Making a home studio recording can be a complicated process if you’re just starting out, and it can get really expensive, too, though you shouldn’t need to surpass $300 if you’re willing to put in the work. The bare minimum for making a home studio recording is treating your room to some extent and making a good initial recording that doesn’t require magic in the mixing phase.

To achieve this, the only things you really need are blankets and pillows, one good XLR microphone with a pop filter, and an audio interface. Many microphones are more versatile than they seem, and while you’re not going to get a Capitol Records-level recording out of a single mic, it’ll do the job for someone starting out.

If you're only going to purchase one microphone, get the Shure SM58.

You can get a USB microphone if you don’t want to buy an audio interface, but investing in an audio interface will come in handy if you make a habit out of recording music. Often, the best option for beginners is to get a studio bundle like the Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 Studio (4th Gen) which comes with an audio interface, headphones, and a microphone for only $300.

Now that your song is recorded, it’s onto the mixing process!

Frequently asked questions about Home studio recording: Everything you need to record on a budget

You’ll reach a point of diminishing returns pretty quickly with things like expensive cables. So, you can afford to cheap out on cables; save that money for something else like a good audio interface or microphone. There are also a lot of free plugins that work pretty well out there. If you’re just tracking live instruments and sending your stuff to someone else to mix, you can probably go with a cheaper version of most DAWs because you just need to record, as opposed to deep editing.

Thank you for being part of our community. Read our Comment Policy before posting.