All products featured are independently chosen by us. However, SoundGuys may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links. See our ethics statement.

How to equalize: Fine-tune your listening experience

March 27, 2025

Before a song makes it onto your playlist, it will have been mastered to optimize playback across as many devices as possible. Audio engineers know how to equalize (EQ), so the music will sound just fine in most scenarios. While not all playback systems are ideal, if you know what you’re doing, you can make your music shine on your gear with a few simple tweaks.

- on May 29th, 2023, for formatting

- on March 27th, 2025, to ensure the information is current and correct.

What is an equalizer?

Before we get into the gritty details, it’s probably best to go over what an EQ is. EQ is an abbreviation of equalizer (or equalization) and is generally defined as the process of adjusting the relative levels of the different frequency bands of an audio signal. To EQ audio to your taste means you need to change the levels of the different frequencies so that when combined, they give you the tonal balance you’re looking for.

The bass and treble controls on car audio systems are basic EQ controls: each knob takes a set range of frequencies and allows the user to alter the relative level of each. Equalizers get more advanced once you dip your toe into more advanced consumer electronics and recording equipment. By adjusting these sliders or turning these knobs, you can control the output of a given frequency range, letting you tweak the sound coming from your equipment.

Why should you use an equalizer?

There are two main reasons why you should equalize your music, and they are not mutually exclusive.

- Preferences determine if you want to EQ and how you want to do it. Everyone hears things a little differently because of the physiology of the human ear. This can also encompass loudness preferences. What sounds good for most people could sound even better if you know what to do. And we all know you’re the only person that truly matters, right?

- The playback system also affects what an “optimal” adjustment is. Nothing is perfect, and you might find your headphones or speakers have a quirk or deficiency that doesn’t sound quite right. If it’s not too serious, then chances are you can account for that quirk when you EQ.

Keeping things in small increments at first will help you get your feet wet when making more aggressive changes later. Chances are good that you won’t need to tweak and adjust much once you’ve found your preferred settings.

Should you use EQ presets?

Some apps and software come with built-in presets, which can be a helpful starting point when learning how to EQ. EQ presets exist for a reason and are generally made by professionals. A good place to start is by selecting your favorite preset and then making minor tweaks from there. It’s easier than starting from scratch but still gives you a tailored sound profile.

Some apps, like Neutralizer for Android, make it super personal by letting you do a hearing test beforehand to see which frequencies matter the most to your ears. For desktop, there’s also Voicemeeter by VB-Audio or Equalizer APO. There’s nothing wrong with using a preset! If you want to dig deeper beyond just learning how to EQ, keep these tips in mind, and you’ll be fine.

If you’re looking to save time, this is a good place to go unless you’re chasing something that can’t be bought.

Is there a technique for creating a custom EQ?

There are two main adjustment types when learning how to EQ. The first is to make the target frequency louder by raising a specific range’s level (amplitude). This is called boosting. It makes sense if you think about it, you’re just boosting the output of something that you want to hear more of. On the flip side, you can also decrease the output of a specific frequency range for something you want to hear less. This is called cutting.

Cutting is usually a better approach than boosting

Cutting is usually a better choice than boosting. If you boost too much, you can introduce distortion, which defeats the purpose of what we’re trying to accomplish here. In short, it’s better to cut the frequencies that you want quieter than boosting the ones you want to hear more of. Done correctly, this will give you the best result while avoiding the pitfalls of boosting too much.

If you see a setting for “preamp gain,” be sure to bring that setting down by the same amount as your largest boost. For example, suppose you boosted 200Hz by 3dB. In that case, you’re going to want to bring the overall preamp gain to -3dB to ensure that your signal isn’t affected negatively by clipping, distortion, or other annoying consequences of pushing a signal too much.

Because this will also reduce the overall level of your signal, huge variations from your original settings are also something to avoid. We try to keep our EQ adjustments at no more than 6dB in either direction, but if you know what you’re doing, you can absolutely go beyond that if needed.

Additionally, don’t boost above 12.5kHz if you can avoid it. It can be very easy to unintentionally make tough-to-hear sounds super loud. Though it’s not likely, it is possible to damage your hearing with loud sounds that you can’t hear, so don’t get too crazy there unless you’re cutting those ranges entirely.

What do I need to know in order to equalize sound?

Now that we know what an EQ is, we can start getting into how to actually use one.

Graphic EQ, or sliders

With most EQ apps on Android, you’ll likely see a system of slider inputs to adjust specific ranges. These inputs are a bit clunky, and they don’t allow very granular control of how you adjust your sound. However, they’re better than nothing, and can usually correct for some of the big issues you’ll find with your music and other content.

These sliders are basically a digital graphic equalizer. Each slider will adjust a preset range of frequencies, with the label hopefully telling you the center frequency of the affected band. It’s not always clear how nearby frequencies will be affected, but at a basic level this is how you’ll be making adjustments.

Moving the sliders up will boost the range, and sliding it down will cut it. Though this type of interface is limited, it is very intuitive. Just be aware that you won’t be able to use the filter types mentioned below to adjust your tunes.

Parametric equalizer

The real magic happens with parametric equalizers, as this type of interface will allow much more granular controls of your sound. With a parametric equalizer, you can define the exact frequency you want your adjustment to center on, while also defining just how broad or narrow of an adjustment you want to make. This type of interface is definitely a bit more difficult to get right, but once you do: you’ll be able to get much more exacting results than with sliders. Popular parametric equalizers include Equalizer APO, Peace, and Roon.

There are four parts to each frequency adjustment (called “filters”) in a parametric EQ:

- Center frequency

- Bandwidth

- Gain

- Filter type

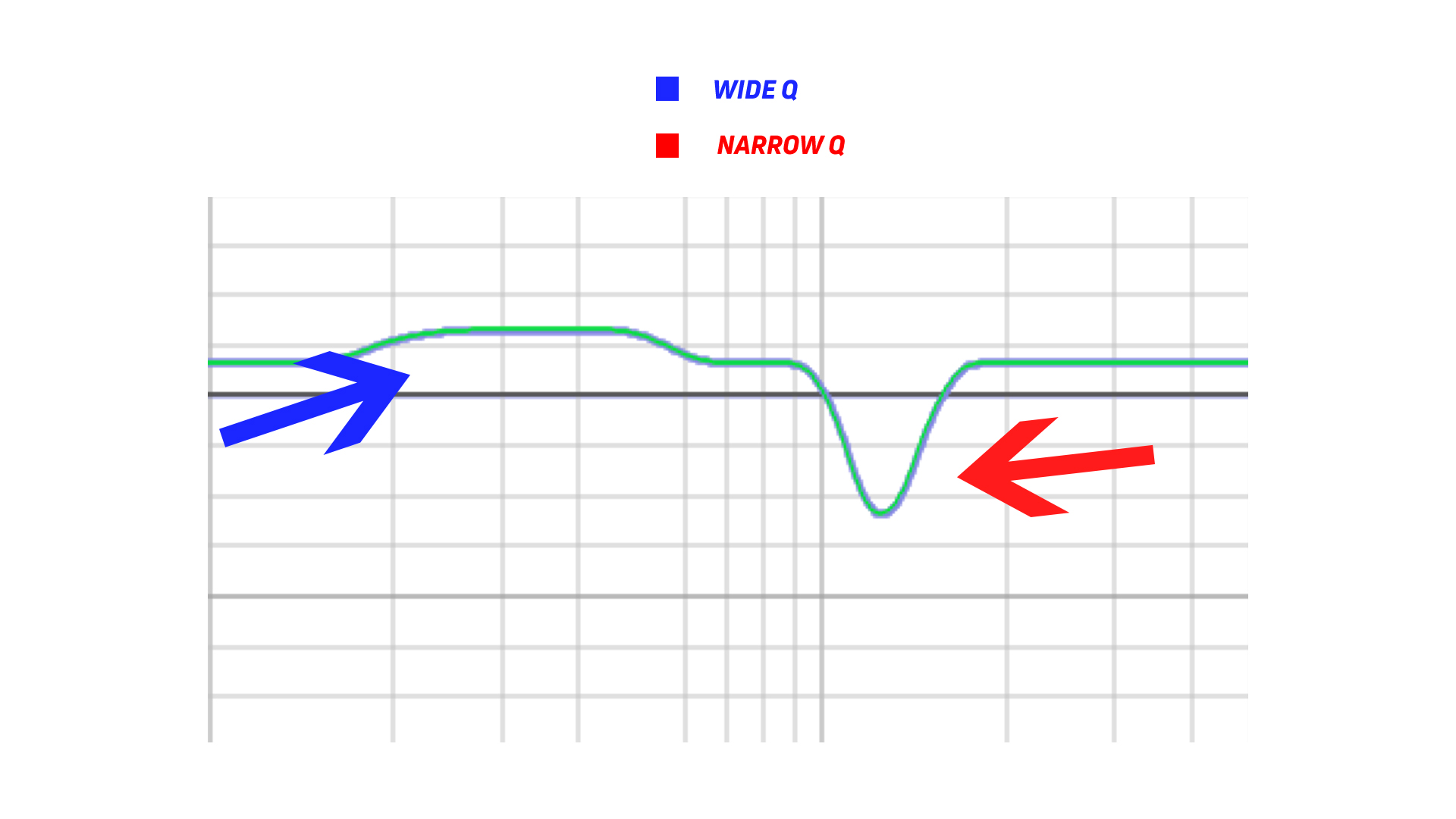

Center frequency selects the specific frequency that you want to adjust. Bandwidth, also known as Q (for quality), refers to how narrow the selection is for the adjustments that you want to make. Those bass and treble knobs you see in cars will usually have a very low (broad) Q, which looks like a small hill when you’re adjusting it. But if you want to target a very specific frequency range, then having a higher (more narrow) Q will let you achieve this. Gain is the of boost or cut that’s applied to the specified range, usually stated in dB.

Filter type refers to the shape of the adjustment. Most parametric EQ programs will offer:

- Peak/Dip: a bell-shaped filter shape

- Low shelf: Adjusts all frequencies below the defined frequency

- High shelf: Adjusts all frequencies above the defined frequency

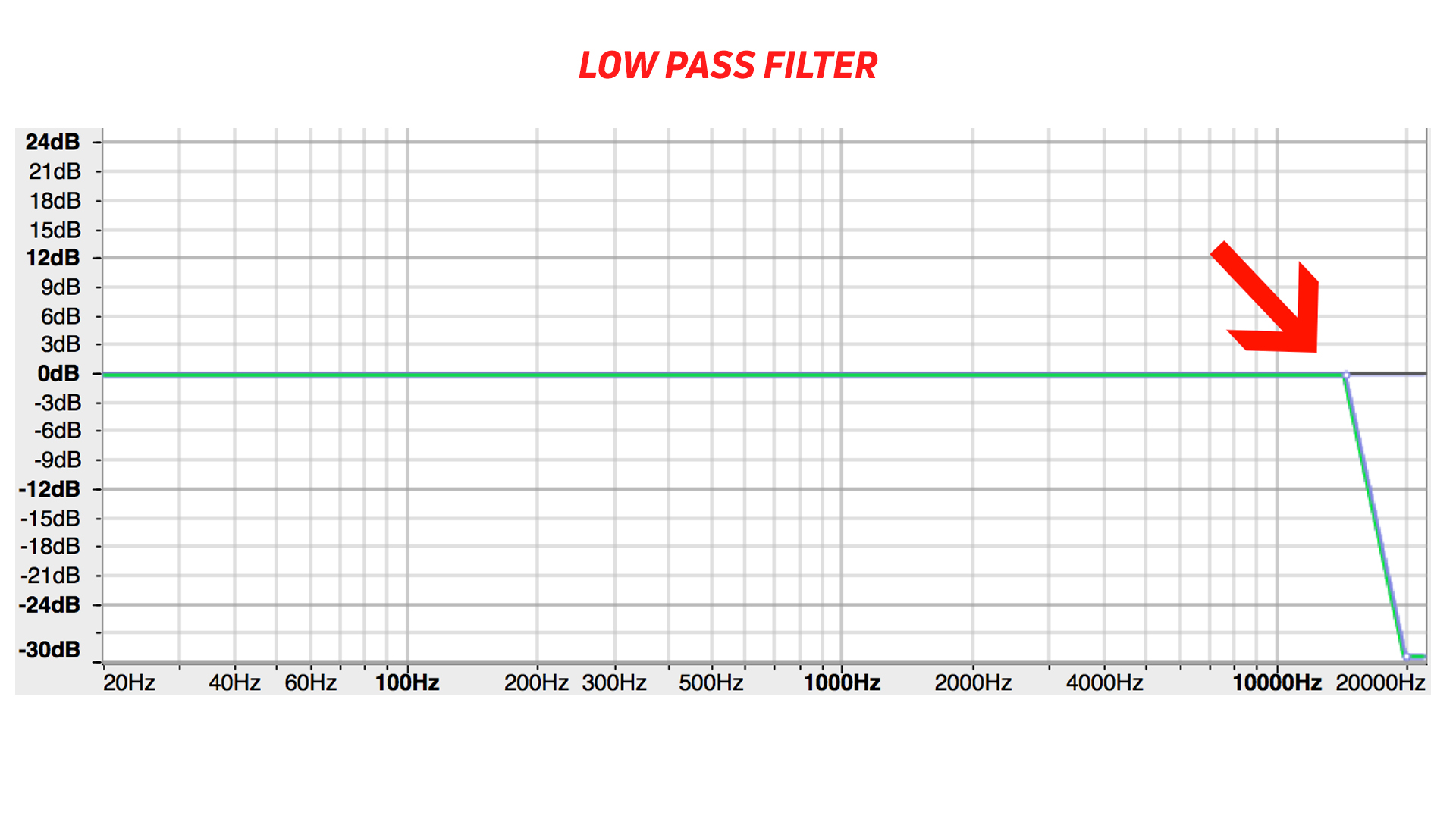

- Low pass: attenuates everything above the defined frequency

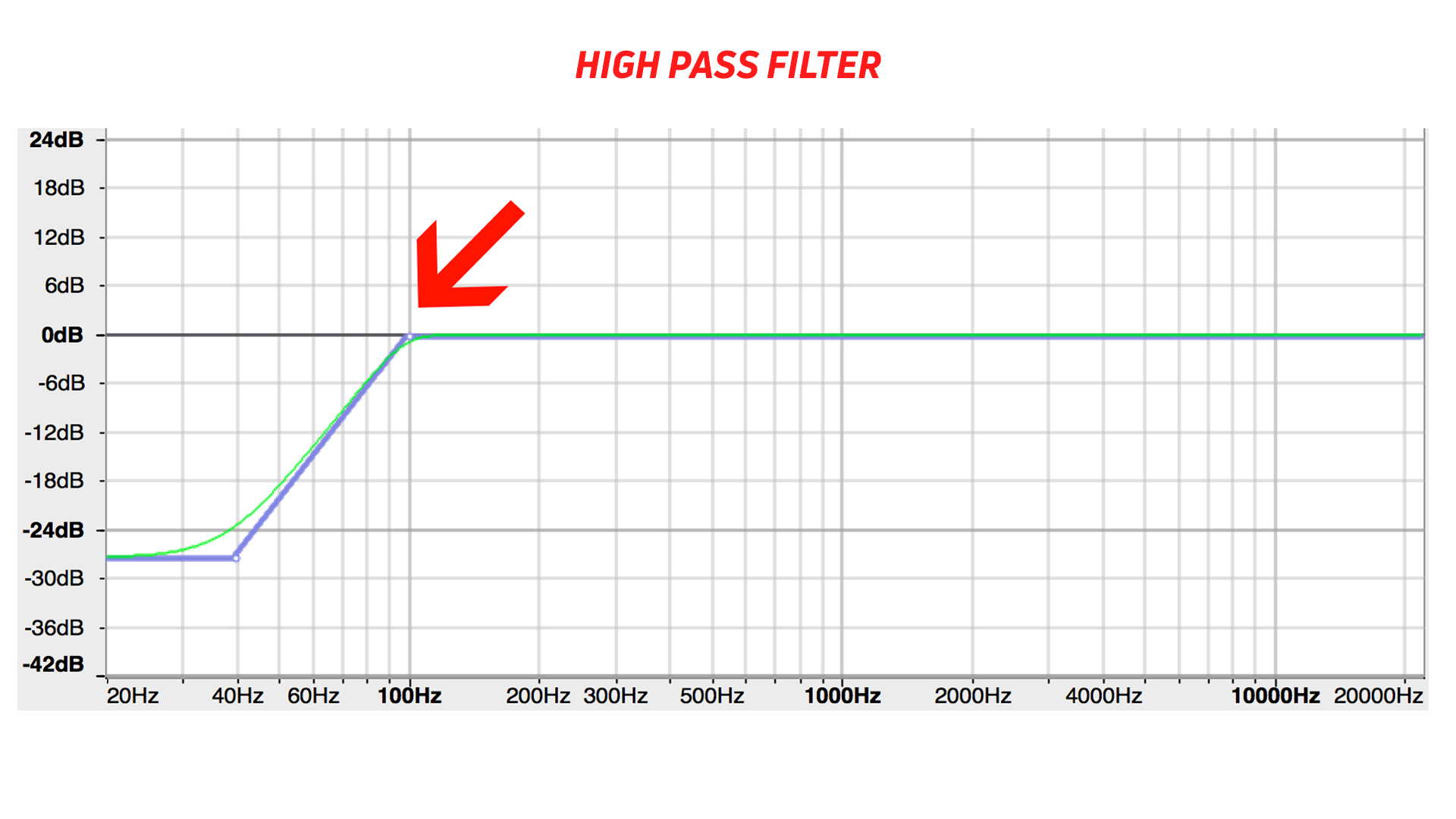

- High pass: attenuates everything below the defined frequency

- Band pass: attenuates everything outside of a defined range

Adding filters to your parametric EQ program should be pretty straightforward, but many people are turned off by having to input lots of numbers or adjust multiple knobs. Most programs will allow you to enable and disable filters on the fly so you can hear the before and after.

What if the new EQ curve sounds weird?

Trust your ear: sound is a very personal experience: things sound a bit different to each person, so everything from here on out, regarding how to EQ, is just a guideline to help find what works best for you. Keep plugging away and don’t be afraid to delete or revert changes you’ve made if they don’t improve your experience.

What are the important frequency ranges for EQ creation?

Whether you want more bass or less cymbals, you should know more or less where their frequency ranges lie. If you want to get granular with it, we recommend checking out this interactive plot that puts the individual instruments in context so you can get an idea of which frequencies to pay attention to.

Notice how almost all of the instruments lie below 10kHz, save for cymbals and hi-hats which can go a bit higher. Sub-bass is usually considered to be between 0- 80Hz, and though it’s harder to hear: you’ll physically be able to feel the air being pushed if you have a large enough woofer. Then there’s the kick drum and bass guitar fundamentals that mostly reside between 60-250Hz.

Adding emphasis around 2kHz usually makes the attack of picked guitar strings easier to hear. Amplifying the 8-16kHz range makes it easier to hear overtones and upper harmonics, something our brains perceive as “clarity” even if it doesn’t actually make the sound higher in quality. Obviously the reverse applies as well, and bumping anything in the 20-250 Hz range gives you a low-end thump that would make Dr. Dre proud.

If you want to test how good your hearing is, we generated a few sine waves here. We can technically hear anywhere from 20Hz-20 kHz, so we made four that give you a broad idea of what you’re listening for (20Hz, 250Hz, 2kHz, 16kHz).

How do I EQ my music?

Now that we know all the parts, it’s time to put it all together.

Rather than looking for the parts of a track that you like and then boosting them, find the parts of the track that bother your ears. Then, cut them. Try to remember that the music itself is mastered in the way it should be: you’re trying to eliminate the unwanted stuff introduced by your headphones or speakers. Make sure the EQ program you’re using has a graphic representation of the frequency response of the output so you can compare that line to the measurements we provide in our headphone reviews. You can use our charts as a general guideline, but equalizing directly to our preference target isn’t guaranteed to get you the results you’re looking for.

Cut off highs (low-pass filter)

Some audiophiles might think they need headphones that can reproduce sounds well above 20kHz, which is highly questionable. Humans can only hear up to 20kHz if they’re young (much lower if they’re not). Set your frequency to just past the point where you can’t hear anything, then add a low-pass filter at that frequency.

Get rid of the extreme lows (add a high-pass filter)

Just like how there’s no point to having anything above 20kHz, it’s really hard to hear anything below a certain point as well, especially over speakers if you don’t have a fire sub-woofer and some bass traps. So unless you’re a basshead, try cutting your EQ curve at around 40Hz. Do this by adding a high-pass filter in your parametric EQ settings at a point somewhere between 30-50Hz.

Eliminate unwanted peaks (add peak filters)

This is the most laborious part of the equalizing experience. Depending on your headphones, you’re going to be making multiple filters here, but the process is the same for all of them. With a high Q (narrow), and sweep through the approximate ranges of frequencies in which they lie until you find a noise that’s particularly harsh or conflicts with something else that you want to have more prominence. Then, you can lower the Q value a bit and cut that part down. Start with a small cut and increase until the offending range no longer sounds out of whack with the rest of your music. Be sure to test this new filter with a couple songs so that you don’t unintentionally make all your tunes sound off in order to save one song. Repeat this process as necessary.

Adjust bass for your liking (optionally add a bass shelf filter)

Many people assume that they want more bass, but it’s actually not always necessary. Sometimes oddities in the higher ranges sound comparatively louder with respect to the bass, making it more difficult to hear. When you’re done with the peak filters, you may find that bass sounds much different than it did before you started. This is normal. Consumer headphones can boost bass quite a bit, so if you’re hearing that for the first time: it can be a bit jarring.

However, if you’ve made the above filters and you still find that bass is lacking, a common adjustment is the bass shelf. Pick this filter, then input a center frequency of 90Hz and then adjust the level between -5 and +5 dB until your music sounds better than it did. Experiment as you see fit, just be aware that you shouldn’t add multiple bass shelves.

This gets rid of the unsavory aspects of your music without introducing noise and distortion, something that often happens with heavy-handed boosting. When you’re done, you can raise the overall master volume up to a pleasing volume and enjoy your customized listening experience.

Thank you for being part of our community. Read our Comment Policy before posting.